By Andrew Nurse

The recent death of David Blackwood has drawn a remarkable and emotional response. Both he and his art seem deeply treasured by those who knew him. Tributes have already praised his work and re-asserted his position in the forefront of modern Newfoundland art.[1] The goal of this post is not to repeat those conclusions; I see no reason to question them. Instead, I’d like to reflect on Blackwood’s art from a different perspective that draws it into conversation with the work of his better-known contemporaries, like Christopher Pratt and Alex Colville. What this conversation indicates, I think, is that Blackwood’s art carries with it different kinds of implications and messages.

Blackwood was born in 1941 in Wesleyville, Newfoundland a small community on Bonavista Bay. By all accounts, he was “a natural.” He opened his own studio while still in his teens and before completing his formal studies at the Ontario Art College, from which he graduated in 1963. After graduating he became art master at Trinity College School and moved to Port Hope, Ontario, where he lived until his recent death. Throughout most of his life, Blackwood also kept a studio in Wesleyville. The life, character, and history of the outports and their people are the subject matter for which he is best known. He was named to the Order of Canada in 1993 and, among other honours, held honourary degrees from the University of Calgary and Memorial University.[2]

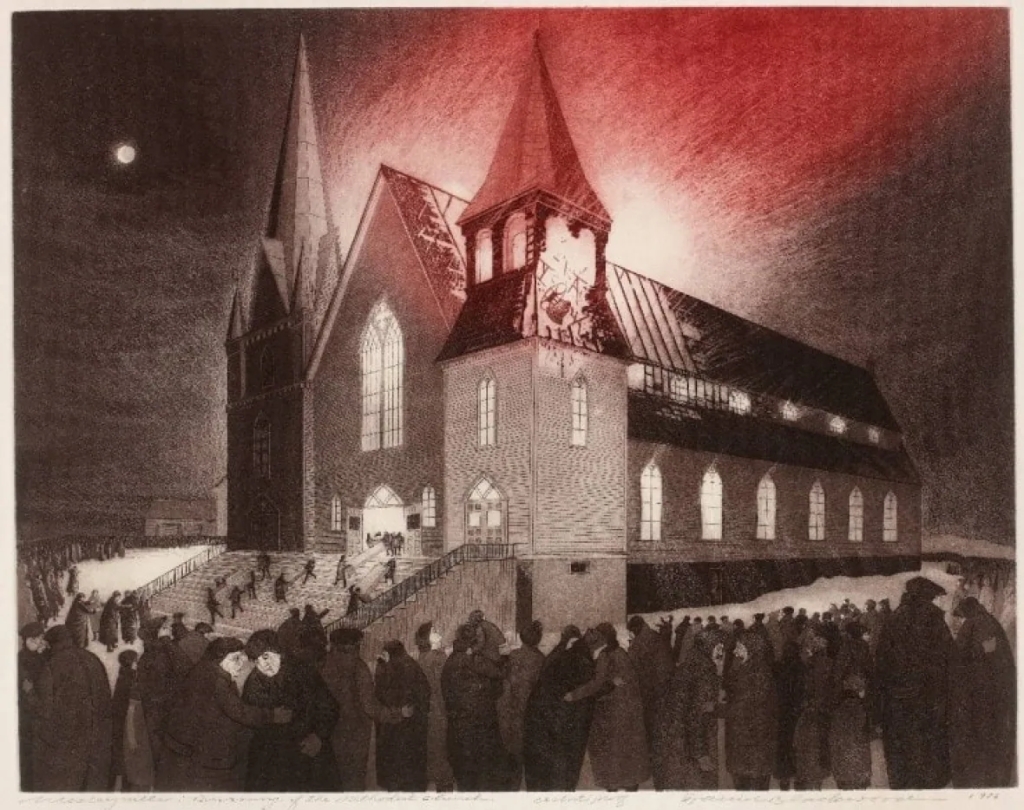

Blackwood worked in a range of media but is best known as an etcher and print maker, a highly technical, time-consuming, and detail-oriented art form, the specifics of which are well captured in a short NFL documentary on him produced in the 1970s.[3] Blackwood’s career is historically interesting for several reasons. There is a haunting familiarity to his art even if he himself remained obscured by the better-known artists of his time. I suspect most people will recognize his work “Hauling Job Sturges House” from the cover of Annie Proulx’s bestselling novel The Shipping News, even if they could not readily name the artist or its subject matter. Despite his early popularity and the critical acclaim of his work, no comprehensive show of Blackwood’s art was held until 2011.[4]

I find Blackwood’s art challenging. This might be because of his medium, which tends to receive less attention than other art forms, or his reduced use of colour, which creates an impression of stark coldness. I also think his work is challenging because his subject matter is deeply grounded in history. Knowing the specific events Blackwood depicted is important to understanding “Hauling Job Sturges House” or “Gram Glover’s Dream,” another of his better-known works. Both represent the post-World War II state sponsored relocations that moved approximately 20 000 Newfoundlanders from smaller to larger communities.[5] His extended “The Lost Party” series represents the 1914 Newfoundland sealing disaster or, more properly, the memory of it. Finally, Blackwood’s art is challenging because it is often organized around narratives that ask his audience not simply to look at his picture but to follow a plotline that can lead in several different directions simultaneous or, in some cases, remains unfinished. Said differently, he produced complex work.

Perhaps the work of his I like the most is “Fire Down on the Labrador” (1980). This print shows a deeply dark nighttime image of a crew fleeing a burning fishing ship in a small vessel that is now a lifeboat. The fire and lifeboat are set to the viewer’s right. The image’s background is occupied with night sky and dark water. A huge baleen whale is foregrounded in the centre below the waterline set against the outline of an iceberg that protrudes above the surface of the water.

“Fire Down on the Labrador,” – along with other words like “The Lost Party” series — capture the dangers of working life in rural Newfoundland. Blackwood respects these people. They are, in his words, “very capable people.”[6] But his respect of people, their skill, and courage becomes neither a romanticized lament for a past time nor celebration rurality or tradition. “Hauling Job Sturges House” illustrates the time and work of relocation that was an unspoken assumption of the policy. It was the time and labour of working people that enacted government policy.

“Fire Down on the Labrador” also illustrates the relationship between Newfoundlanders and their environment. There is something almost insignificant, as Michael Crummy has noted, in the human dimension of this image.[7] The people are lost against an environment that does not seem at all interested in them, but which poses a clear danger to them. His images tell us something of Settler society and its relationship to a natural environment it could never fully master. His work combines elements of awe, respect, wonder and fear. Moreover, as viewers of this image, we never know what finally happened. Did the crew return safely to land? Were they upended? Could they survive the cold?

I also think Blackwood’s art troubles easy conceptions of modern Atlantic Canadian art history. It seems to me that his focus on skill, detail, and craft lends a different critical discourse to his work than that which surrounded artists like Colville or Pratt. Colville, for instance, was often presented as genius. A more standard perspective on Blackwood is that of a storyteller.[8] Perhaps because I am an historian, I like that characterization. At the least, Blackwood’s art shows the diversity of post-World War II Atlantic Canadian art, the vitality of a tradition of social engagement, and a continued interest in representing the lives of working people. If we compare this to the image-oriented art practiced by, say, Colville, we can see that there is a very different perspective at work. The fact that Blackwood could leave the story unfinished also strike me as important. Instead of asking us to look at a scene, he draws us into the potentially fraught and unfinished lives of ordinary people. That alone could be reason take the time we should with this art.

Andrew Nurse is a Professor of Canadian Studies at Mount Allison University

[1] Andrew Hawthorn, “David Blackwood, Iconic Newfoundland Artist” CBC, 3 July 2022 <https://www.cbc.ca/ news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/blackwood-obit-july-2022-1.6509080> (accessed 7 July 2022); Mireille Eagan, “David Blackwood’s Death Leaves Great Void in N.L. Culture, Curator Says,” 5 July 2022, CBC News <https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2049269315865> (accessed 7 July 2022).

[2] Details on Blackwood’s life can be most easily found through his web site “David Blackwood” <http://www.davidblackwood.com/home/> (accessed 20 July 2022). See also Sarah Smellie, “Canadian Artist David Blackwood, Known for Etchings of Newfoundland Life, Dies at 80,” Thestar.com (4 July 2022) <https://www. thestar.com/entertainment/2022/07/04/canadian-artist-david-blackwood-known-for-etchings-of-newfoundland-life-dies-at-80.html> (accessed 7 July 2022).

[3] Tony Ianzelo and Andy Thomson, “Blackwood”, 1976, National Film Board <https://www.nfb.ca/film/ blackwood/> (accessed 14 July 2022).

[4] Sara Angel, “David Blackwood Finally Gets His Moment in the Sun,” Macleans.ca (9 Feb

ruary 2011) <https://www.macleans.ca/culture/forty-years-later-a-moment-in-the-sun/https://www.macleans.ca/culture/forty-years-later-a-moment-in-the-sun/> (accessed 20 July 2022).

[5] Bonaventure Fagan, “Images of Resettlement” Newfoundland Studies 6,1 (1990), 1-33.

[6] David Blackwood “Heffel in Conversation: David Blackwood,” by Daniel Gallay Heffel 23 September 2020, Youtube video 41:31, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UpGOcyROPKQ> (accessed 14 July 2022).

[7] Comment from “Fire Down on the Labrador by David Lloyd Blackwood” Cowley Abbott <https://cowleyabbott.ca/ artwork/AW29285> (accessed 20 July 2022).

[8] Eagan, ” David Blackwood’s Death Leaves Great Void in N.L. Culture.”