By Tabitha Renaud

Much of what historians know about early contact between European explorers and indigenous peoples in northeastern America comes from close readings of the surviving explorer journals of the sixteenth century. European expedition narratives generally “translate” indigenous “speakers” with great confidence. Contemporary authors often recorded native speech as if no language barrier existed and perfect transmission of information was occurring. Explorers often wrote “he said” or “they say” without alluding to the level of gesticulation, interpretation, mediation and guesswork involved. A standard example is found in the writing of Ralph Lane during the Roanoke encounters with the Carolina Algonquin:

But this confederacie against us of the Choanists and Mangoaks was altogether and wholly procured by Pemsiapan himselfe, as Menatonon confessed unto me, who sent them continual word, that our purpose was fully bent to destroy them: on the other side he told me, that they had the like meaning towards us.[1]

If miming is acknowledged in such texts the act of deciphering is treated with a similar confidence. George Best wrote during an arctic expedition in 1577 that an Inuk “gave us plainely to understand by signes that…”[2] Similarly, Ralph Lane wrote at Virginia that “hee signified unto mee…” and John Davis wrote at Greenland: “…as by signes they gave us to understand…”[3] In various expeditions the element of interpretation is vaguely alluded to but not considered problematic: “It seemed to me by his speach that…” and “we judged…” and “…the best conjecture we could make thereof was that…”[4] At Gaspe in 1534, Jacques Cartier indicated the interpretation of the “long oration” of an indigenous leader with the words: “…as if he would say that …”[5] Nevertheless, the accurate transmission of information was typically taken for granted by contemporaries and became the building blocks that comprise the “known facts” of these case studies today.

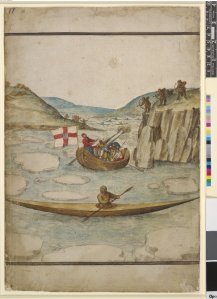

Francis Back, First Contact.

Despite its centrality to understanding early contact, the initial phase of communication between European explorers and indigenous peoples has been understudied by historians. Scholarship has focused primarily on the acquisition of spoken language and the training of spoken language interpreters. The evidence surrounding the initial nonverbal forms of communication is often considered lost, too fragmentary or beyond the training of historians. Ives Goddard aptly states,

The specific characteristics of the means of communication can be expected to have had an effect on the content and quality of communication and to reflect aspects of the encounter, yet scholars have typically shown little interest in exploring this topic. It seems generally assumed that some individuals would have learned the language of the other group and served as interpreters.[6]

An examination of the mechanics of how communication functioned during the earliest recorded encounters suggests this historiographical assumption needs to be revisited.

A close reading of early explorer journals reveals descriptions of the various forms of nonverbal communication the two peoples experimented with during their earliest interactions. A passage from an encounter between the Elizabethans and the Greenland Inuit in 1585 is representative of some forms of communication utilized and how they appear in the source base:

When they came unto us, we caused our Musicians to play, our selves dancing and making signes of friendship… they talked with us… Their pronunciation was very hollow thorow the throat and their speech such as we could not understand: onely we allured them by friendly imbracings and signes of curtesie. At length one of them pointing up to the Sunne with his hand, would presently strike his breast so hard that we might heare the blow. This hee did many times before he would trust us…[7]

Both explorers and First Peoples used sound, symbol, objects, gesticulation, illustration, demonstration and their actions to communicate. Mimicry, reciprocation, repetition and observation were also important approaches implemented. Moreover, vocabulary lists were sometimes included in French and English narratives indicating both the nature of communication and the lack of complexity. It is telling that the vast majority of words were simple nouns and verbs that could be easily demonstrated in the moment. Nevertheless, even gesticulation that seems readily apparent can be easily mistaken. Are they indicating the noun “ear” or the concepts of “hearing” or “understanding?” An Inuk thought to have conveyed the noun “needle” appears to have actually stated the item belonged to his daughter.[8]

It is important to understand that creating and interpreting messages of this nature is incredibly subjective and relies on impressionistic guesswork that is rooted in each communicator’s assumptions and expectations in the moment. It is easy for miscommunications to occur as parties think they comprehend when they might not. Whatever signs of affirmation or negation one receives, the effectiveness of transmissions is often unverifiable. The French and English case studies of the sixteenth century all indicate how frustrating and dangerous limited communication could be. The analysis of these interactions today is riddled with unanswered questions and unverifiable hypotheses and historians must tread carefully. However, through close reading more about these cultures, the events in question and the very nature of communication itself can be discerned.

John White, The Skirmish at Bloody Point. Image Source, British Museum, SL,5270.12.

The evidence suggests that despite the confident and sometimes elaborate translations of Europeans, nonverbal communication between parties was problematic in several key areas. Initial communication relied heavily on visual demonstration within direct line of sight. This suggests that invoking invisible topics would have been difficult. Communicators would have struggled to express complex information, abstract concepts or to reference anything that occurred in another time or place. For instance, John Davis’ men could not coordinate the refund of a kayak at Greenland in 1586 as they could not reference the original transaction or explain their intentions. When five crewmen disappeared at Baffin Island in 1576, Martin Frobisher could not reference the men or the event to the Inuit effectively afterwards even with the use of illustrations. It also proved difficult to distinguish between death and absence unless a cadaver was visually presented. The dependence on visual elements meant that the two peoples struggled to make future plans together, reference their pasts or to explain their inner thoughts and feelings. It was difficult to understand what others were doing unless they were physically present. The inability to understand what natives were thinking and doing much of the time arguably contributed to European paranoia and anticipatory aggression that proved toxic for intercultural contact.

Europeans could not verify the identities of local people and communities or their personal and political relationships to each other. This problem was exacerbated by the difficulty explorers had distinguishing between indigenous groups. They could only guess at the complex local political landscapes they inserted themselves into. These visitors also typically assumed any indigenous people found within the same area interchangeably shared the same knowledge, experiences and relationship with them. Mistaken assumptions about who people were, what they knew and what experiences had been previously shared muddled communications and sometimes proved dangerous. All of these challenges would have significantly impacted communication and increased the potential for misunderstandings. This led to the greatest challenge of all: miscommunications could be completely undetectable. These uncorrectable premises could build upon each other invisibly and hinder diplomacy.

In conclusion, this initial phase of communication has been largely glossed over by researchers. Yet we can see glimpses of how the mechanics of this early communication functioned and it raises methodological and epistemological questions that should be explored. The communication barrier is more complicated than we sometimes allow for in our analysis and we should perhaps revisit some of the long accepted facts of well-known case studies. This is an enormous topic and this brief piece serves merely as a point of departure.

Tabitha Renaud is a PhD candidate at Queen’s University whose dissertation examines the English-Indigenous communication barrier in Northeastern America in the sixteenth century.

Notes:

[1] Ralph Lane, “The Roanoke Expedition of 1585-6,” The Principal Navigations. Volume 8. (Glasgow: MacLehose, 1903), 326-7. Emphasis mine.

[2] George Best, “The Frobisher Expedition of 1577,” The Principal Navigations. Volume 7. (Glasgow: MacLehose, 1903), 302.

[3] Lane, “The Roanoke Expedition of 1585-6,” 323. John Davis, “The Davis Expedition of 1586,” The Principal Navigations. Volume 7. (Glasgow: MacLehose, 1903), 398.

[4] Lane, “The Roanoke Expedition of 1585-6,” 323. Davis, “The Davis Expedition of 1586,” 401. Best, “The Frobisher Expedition of 1577,” 301. Emphasis mine.

[5] Jacques Cartier, “The Cartier Expedition of 1534,” The Principal Navigations. Volume 8. (Glasgow: MacLehose, 1903), 204.

[6] Ives Goddard, “The Use of Pidgins and Jargons on the East Coast of North America,” The Languages of Encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800. Edward Gray and Norman Fiering, eds. New York: Berghahn (2000), 61.

[7] John Janes, “The Davis Expedition of 1585,” The Principal Navigations. Volume 7. (Glasgow: MacLehose, 1903), 386-7.

[8] Louis-Jacques Dorais, The Language of the Inuit (Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 2010), 108.