By Ronald Rudin

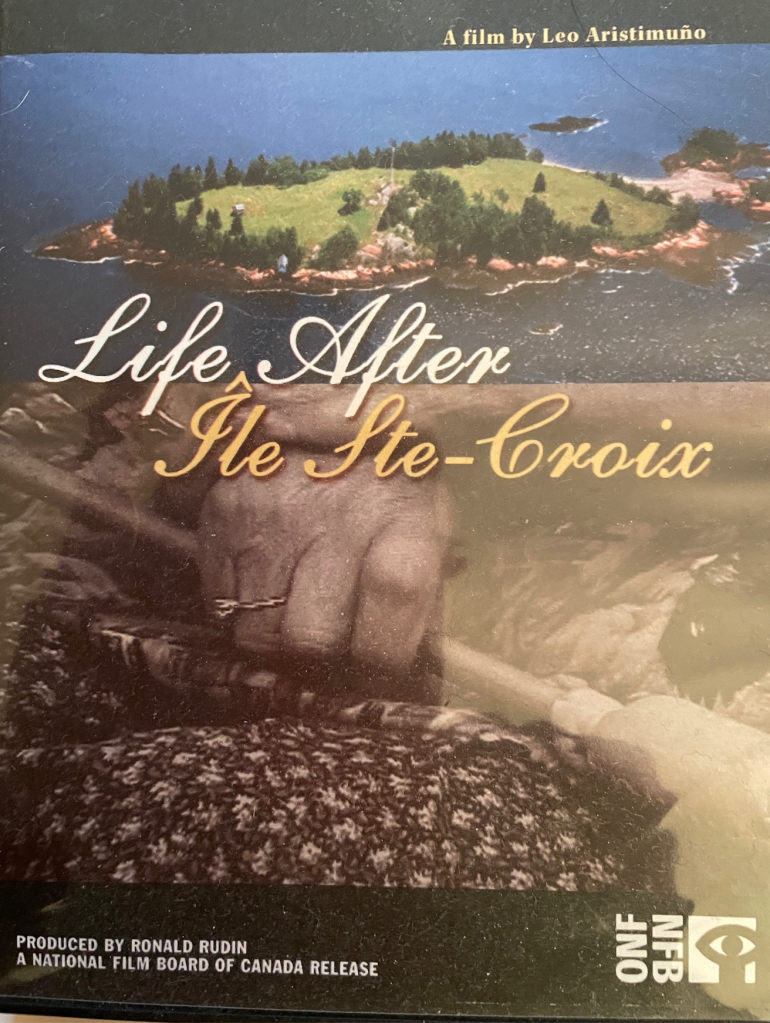

Fifteen years ago, the National Film Board of Canada released a DVD (remember them?) of the film Life After Île Ste-Croix that I produced and Leo Aristimuño directed. The film, and the book that accompanied it, Remembering and Forgetting in Acadie, explored the construction of commemorative events marking the 400th anniversary in 2004 of the first effort by France to create a permanent settlement in North America.

Even though this settlement, on an island that sits on the international border between New Brunswick and Maine, survived only one winter, it has been remembered in various ways. For some Acadians, it marked the beginning of a French-speaking experience in Atlantic Canada. In that context, 2004 provided an opportunity for Acadian leaders to draw attention to a beginning in the early seventeenth century, putting Acadians on the same timeline as other peoples such as the Québécois. For English-speakers, who have long made up the vast majority of the population of the area, the commemorative events provided an opportunity to attract tourists, to show them what destinations such as St Andrews had to offer. Finally, and most importantly, the quadricentenary provided an opportunity for the Peskotomuhkati/ Passamaquoddy First Nation to tell its own story. Long viewed by governments as an American tribe, 2004 allowed the Peskotomuhkati to draw attention to their presence in Canada, where they were not recognized.

Since no one was still buying DVDs, in 2018 I reached an agreement to move the film to the NFB’s online platform where it could be viewed for free, but that arrangement ended in early 2021, forcing me to find a new way for Life After Île Ste-Croix to be seen. As it turns out, in 2006 we constructed a website to offer glimpses — mostly through stills and video clips — of the Île Ste-Croix commemorative events. This site is now the home for the film, which can be accessed directly through this link.

Moving the film to its new home gave me an opportunity to reflect on one of the major challenges of digital scholarship, namely its vulnerability due to technological changes and decisions by organizations over which we have no control. But it also gave me a chance to think about the people I met fifteen years ago. For instance, there is a moment near the end of the film where Norma Stewart, who headed up the local, English-speaking programming in 2004, was closing down her office, now that the events were done. As she explained, her efforts would now turn “100% to the legacy project, the construction of the habitation as described by Champlain,” that would be installed on the New Brunswick mainland, from a site looking out over the island. Fifteen years later, the field, where I stood in the rain for commemorative events, remains empty, with no sign that a tourist attraction is in the offing.

On the other hand, the past fifteen years have seen some significant changes in the status of the Peskotomuhkati First Nation in Canada. When I first went to the region, several years before the commemorative events, I was greeted with snickers when I asked about the role that the Peskotomuhkati would play in the quadricentenary, one local leader scoffing at the notion that there were more than a handful of these Indigenous people in Canada. But in the years leading up to 2004, tribal leaders on both sides of the border, such as Donald Soctomah in Maine and Hugh Akagi in New Brunswick, took the view that they should involve themselves in these events to get the story of the Peskotomuhkati presence on the Canadian side of the border better known. For me, seeing Chief Akagi and Prime Minister Paul Martin speak from the same stage was an implicit recognition that these people did exist in Canada. I wish I could say that the Peskotomuhkati have achieved what Hugh Akagi recently described to me as the “R” word – recognition. And while recognition remains illusive, much has been achieved.

To take one concrete example, in 2018 the federal government acquired a hunting lodge on traditional, unceded Peskotomuhkati land, and gave it over to the tribe so that it might serve the interests of the tribe, perhaps using it as a healing lodge. A photo in a CBC story from the time shows Chief Akagi together with Carolyn Bennett, the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations, standing inside the lodge to mark the transfer. While this might not be recognition, it looks like a serious step along the way. There has been life after Life After Île Ste-Croix.

Ronald Rudin is a Professor Emeritus of History at Concordia University