This is the first of a six-part auto-biographical series about the Cape Breton Development Corporation (DEVCO) by Gerald Wright, who was from 1989 to 1992 a senior policy advisor to the federal minister responsible for DEVCO. [1]

I’ve Been Down Under Ground

Cabinet shuffles engender anticipation mixed with apprehension. In the aftermath of the 1989 shuffle, Tom Hockin, the federal minister for whom I had been working since March 1987, acquired new responsibilities. I scanned the list, my eye fastening on the Cape Breton Development Corporation (DEVCO).

DEVCO had been established in 1967 by an Act of Parliament, both to manage Cape Breton’s coal mines and to pursue industrial development for the region. Shortly before we came on the scene the Industrial Development Division was transferred to Enterprise Cape Breton Corporation, a regional development agency. In the late eighties the corporation was operating three mines: Lingan, the oldest and least cost-efficient, near New Waterford; Phalen, 400 feet underneath Lingan, a “gold-plated mine”, replete with the latest advances in mining technology; and the Prince Colliery, located approximately sixty kilometers distant at the northeastern tip of Boularderie Island.

DEVCO produced metallurgical-grade and thermal-grade coal for both domestic and export markets. The corporation’s competitive disadvantage was the high percentage of sulphur in its coal but the coal retained customer appeal on account of its high calorific value and low ash content.

Coal had been mined in Nova Scotia as early as the 1720s. The French fortress of Louisbourg was heated by coal. In the not-too-distant past as many as twelve thousand men had been employed in the mines. The coal mining culture was deeply rooted, infectious, and tinged with tragedy. No one could remain unmoved attending a Davis Day event every June 11, commemorating those who had lost their lives to coal mining, or hearing old timers tell of the explosion in Glace Bay’s No. 26 Colliery in 1979, in which twelve men were killed. Nor could anyone be immune to the appeal of The Men of the Deeps, the coal miners’ chorus, as they sang about what was in their blood. At the same time, the purchase that coal mining exerted on the emotions was partly responsible for the unreality of much public discourse about the industry.

Coal generated nearly half the world’s electricity. Diehard proponents on Cape Breton proclaimed coal the fuel of the future. In their eyes, to attack coal was to attack the regional patrimony. Imagine the ire of Cape Bretoners when environmentalist David Suzuki, visiting Halifax, described coal as an enemy and its promoters, particularly Nova Scotia Premier John Buchanan, as dinosaurs![2] Suzuki was unwittingly feeding local suspicion of outsiders with their supposedly uncomprehending attitudes and unthinking designs.

The suspicions harboured a shadow of truth. In Ottawa circles, political and bureaucratic, nothing evoked glum looks and glazed eyes as much as mention of a money-losing coal company. I, however, was drawn to DEVCO because it offered such a fascinating mix of politics, economics, society and culture. I enthusiastically volunteered to be point man for DEVCO on the minister’s staff, beginning a three-year, long-distance immersion in the life and politics of Cape Breton. Nothing I ever did in government gripped me more.

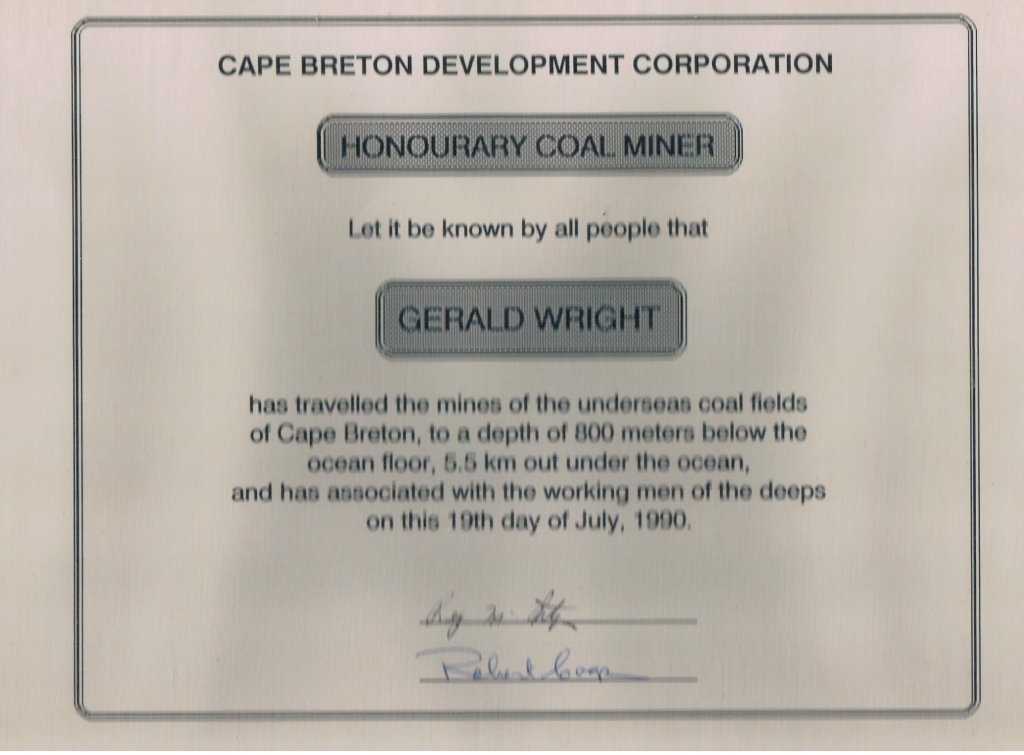

Paradoxically, the grip tightened after I had briefly experienced a miner’s daily grind, joining the minister and others in a tour of the Lingan Colliery. Dressed in orange coveralls, hardhats and rubber boots we were transported by man-carrying trolley 5.5 kilometres out under the ocean to a depth of 800 meters below the ocean floor. Almost from the beginning I began to sweat. When we reached the coalface, DEVCO CEO Ernie Boutilier told us to turn off our headlamps, rendering the tunnel blacker than black. One of our party, a recently defeated Tory candidate, promptly piped up, “This is how I felt on election night.”

A different thought was running through my mind. What would it be like to walk these tunnels day after day, head bent low to avoid uneven roof beams? I was beginning to understand how hardships underground could give an edge to miners’ complaints, real and imagined. A few were known to have risked riding the conveyor belt with the day’s coal production in order to get out faster. Yet how could I square their grievances with the fervent attachment of whole communities to mining as a way of life?

Reaching the top, I shed my coveralls and stood rather sheepishly in the showers, taking in the incongruous sight of naked miners sharing bottles of Johnson’s Baby Oil to flush away the coal dust. In my case it was a losing proposition. When I took off my shirt that night, it was black inside.

Retired after a career in government, universities and a private foundation, Gerald Wright is Senior Fellow of the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs of Carleton University. From 1989 to 1992 he was senior policy advisor to the federal minister responsible for the Cape Breton Development Corporation (DEVCO).

Notes:

[1] The author is grateful to Merrill Buchanan, John Harker, Julie Rickerd and Prof. Andy Parnaby for their advice and assistance, and to the Hon. Tom Hockin for access to his papers.

[2] “The great dino-debate,” The Chronicle-Herald, November 25, 1989